On the way in to work on Tuesday of last week, I dashed off a slightly grumpy LinkedIn post highlighting and decrying the use of AI to write PhD supervision enquiries. Here it is in full:

I am getting more and more enquiries for PhD supervision which have clearly been written using AI. It is very easy to spot. It starts with an abstract summary of my research, highlighting a few of my publications and how transformative the writer has found them. One recent enquirer told me how inspiring they had found one of my papers which has not been published yet, but which appears as in press on my profile. It is that (painfully) obvious. After that is a similarly abstract summary of the applicant’s plans, welded on to the first bit like two halves of a dodgy second hand car, sometimes but not always peppered with a vague research question or two. Many clearly have nothing to do with my own research interests or expertise at all, the only connection being a few buzzwords.

Don’t do this. I will not even respond to such approaches. You are asking me to invest a significant proportion of my career in a close three or four year professional relationship, and I have to know it is going to work. Please therefore do me the courtesy of investing the time and effort to explain your motivation, qualifications and the backstory that has bought you to me in your own words. If you can’t do this, I won’t invest the time or effort to consider your request.

This post, as they say, blew up: as of today (Wednesday 19th November) it now has well over 2000 reactions and over 100 comments, and has been shared over 80 times. I am really grateful for the many, many messages of support I’ve had, both public and private. I am also grateful for the debate which has been sparked. Some of the responses disagreeing with me make valuable points on this important issue. Most of these comments deserve individual responses (there are a small number which do not); but unfortunately there are simply not enough hours in the day for this. In the light of this, I am therefore offering what I hope is the next best thing, which is a slightly more considered post, written with a few days’ space behind it, as well as a careful reflection on the comments which came back. I am posting this here, as it turned out to vastly exceed LinkedIn’s character limit.

Here goes…

The first thing I think I should make clear is that I am not “Anti-AI”. You may as well be Anti-Internet, or Anti-Email (well now I come to say that…). I also have the self-awareness to know that many, probably most, of my own interactions online are, to one extent or another, informed and/or framed by AI. And I am not against the use of AI in a PhD thesis, or indeed any other research context. If someone were to come to me with AI as part of their research plan, our first conversations would include questions of why and how it would be used (in that order), which methods and models, what value would it bring, the literature it would draw on and – crucially – how its use will be made transparent to the thesis’s eventual examiners and in any publications arising from it. I do not know everything, and I expect that I would have much to learn from a good PhD student who understands the issues about these things. I would be keen to do so.

I do not, however, think this is the same as using AI to uncritically concoct communications with me, which should reflect nothing but the candidate’s own perspectives, ideas and vision. Otherwise the approach is at best inauthentic, and at worst deceiving. In the case I highlighted in the LinkedIn post, I was told that a publication that appears as “in press” on my profile had inspired and driven the applicant’s thinking. This could not possibly be true, as the paper has not been published yet. We can have a conversation about whether this statement was the applicant’s voice, or AI’s (or the LLM’s, if the distinction is useful), and how these things interrelate. This example is not, however, about improving structure, narrative or presentation, or any of the other things AI is supposed to be able to do: when they copied and pasted that text into an email, typed my email address in, and pressed “send”, they took responsibility for it – and thus for telling me an untruth. I won’t apologise for finding this problematic; and I think I am within my rights to question any other statement in that email as a result.

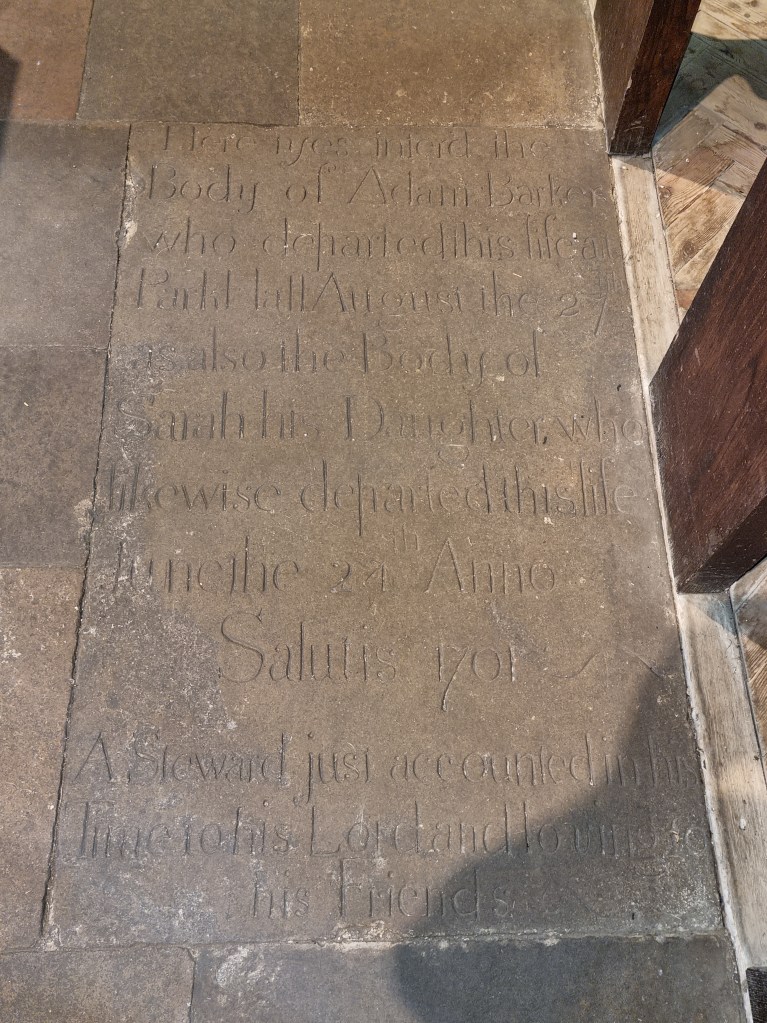

I agree, however, that a specific bad use of AI does not mean that AI itself is bad. This is a broader truth about reactions to innovation. Wikipedia is about to celebrate its twenty-fifth birthday. I recall the angst and jitters that it caused in its first few years, with some predicting that it would drag down the very integrity of the world’s knowledge, seeing it as a new-world embodiment of amateurism (in the most pejorative sense of the word) and non-expertise, the polar opposite of everything that the peer review system is supposed to safeguard. Ten years or so ago, I spent some time working in various roles countering and managing student academic misconduct. Almost all the cases I dealt with were plagiarism, and a large proportion of these involved unattributed copying from Wikipedia. Despite this, as it has turns out, Wikipedia has evolved an imperfect yet functioning editorial model, a foundational funding basis which has the biggest of Big Tech’s beasts rattled (billionaires really hate sources of information that they can’t control, especially when it comes to information about themselves), and I believe that the world of open information is better, rather than worse as a result of it. As a by-the-by, I could add the important qualification that while Wikipedia has staunchly defended its independence from multinational Big Tech interests, AI is a product of them. This is potentially a significant point but, for now, is part of a different conversation.

The truth is that Wikipedia is valuable resource, and that there are entirely correct and appropriate ways of using it in scholarship. There are also entirely wrong and inappropriate ways. As I see it, the unattributed copying of Wikipedia by students that I dealt with did not confirm the sceptics’ worst fears, rather it highlighted the need for those students to be taught this distinction, and highlighted our own responsibilities as educators to do so. My strong suspicion is that in the next twenty-five years, and probably a lot less than that, we will find ourselves on a similar journey with AI. The questions will be about the appropriate ways to use it, what benefit these actually bring, and, most importantly, how accountability is maintained. For example, if one were to ask ChatGTP to “write a literature review of subject X”, once one had checked all the sources found – for example to make sure that they have actually been published(!) – cross-referenced them, and ensured that the narrative actually reflects one’s own mapping of subject X, then I am not sure what one will actually have achieved in terms of time or effort saved, assuming that one does not try to pass off the synthesis as one’s own. I assume most of us could agree that would be a bad thing. But maybe I am looking in the wrong place for those benefits. I just don’t know.

The PhD, certainly in the domains I am familiar with (the humanities), has served as a gold standard for academic quality for centuries. Does that mean it a museum piece which should never be re-examined or rethought? Absolutely not. There are many interesting things going on with PhDs in creative practice, for example, and the digital space. Proper and appropriate ways of using AI in research certainly exist alongside these, but we need to fully understand what these are. If there is to be an alternative to the “traditional” PhD (and to “traditional” ways of doing a PhD) then something better has to be proposed in its place. It is not enough to simply demand that academia, or any sector, just embrace the Brave New World, because Progress.

One thing I do not believe will, or should, change however, is the fundamental importance of accountability and responsibility, and of not ceding one’s own agency. Several of the comments taking issue with my post suggested, correctly, that if the AI had been used well, I would not have noticed it. So, if you do use AI to write that first email to me, make sure that you have read it, have taken full ownership of it, and ensure that it does indeed reflect your own perspectives, ideas and vision. If you do that, and are confident that you have taken accountability and responsibility for it, then I guess it is no more my business if you have used AI or not than if you had, say, used a spell checker. That is the difference between using AI to help you and getting AI to do it for you.

Oh, and if you want to support Wikipedia by donating to the Wikimedia Foundation, as I occasionally do, here is the link.